ADVERTISEMENT

Mastering The Akin Osteotomy

Although the Akin osteotomy has limited use as an isolated procedure for surgeons, it is still a valuable adjunct procedure. This author explores when to perform an isolated Akin and which procedure to choose, offers a guide to effective fixation and discusses how to address an overcorrected Akin.  The Akin is the best bunion procedure to perform in conjunction with another bunion surgery.1 By itself, the Akin bunionectomy has limited utility in today’s practice. The benefit of performing a concomitant Akin is to gain additional correction of the big toe. However, it is important to understand the limitations of the Akin and how over-reliance on the Akin can lead to a failed bunion surgery. An Akin is a hallux osteotomy of the proximal phalanx for the purposes of correcting an abduction deformity of the big toe. Since surgeons first utilized the Akin with bunion deformities, the term “Akin bunionectomy” is commonplace. In the early years of bunion surgery, prior to advanced internal fixation and bone cutting techniques, the Akin was a hallmark procedure for correcting bunions by realigning the big toe only, doing nothing for correcting the true cause of a bunion, which is mostly a malaligned first metatarsal bone. The Akin gave the appearance of correcting a bunion by producing a straight big toe.

The Akin is the best bunion procedure to perform in conjunction with another bunion surgery.1 By itself, the Akin bunionectomy has limited utility in today’s practice. The benefit of performing a concomitant Akin is to gain additional correction of the big toe. However, it is important to understand the limitations of the Akin and how over-reliance on the Akin can lead to a failed bunion surgery. An Akin is a hallux osteotomy of the proximal phalanx for the purposes of correcting an abduction deformity of the big toe. Since surgeons first utilized the Akin with bunion deformities, the term “Akin bunionectomy” is commonplace. In the early years of bunion surgery, prior to advanced internal fixation and bone cutting techniques, the Akin was a hallmark procedure for correcting bunions by realigning the big toe only, doing nothing for correcting the true cause of a bunion, which is mostly a malaligned first metatarsal bone. The Akin gave the appearance of correcting a bunion by producing a straight big toe.  As surgeons moved toward bunion correction with metatarsal osteotomies, they would perform the Akin when the metatarsal correction was “not enough” to produce a straight toe. In this situation, the Akin was a “cheat” to the metatarsal bunion procedure, leading to the term “cheater’s Akin.” Today, we consider the terminology “Akin bunionectomy” outdated. The correct terminology to use is “Akin procedure/osteotomy” or anatomically as a “hallux osteotomy.”

As surgeons moved toward bunion correction with metatarsal osteotomies, they would perform the Akin when the metatarsal correction was “not enough” to produce a straight toe. In this situation, the Akin was a “cheat” to the metatarsal bunion procedure, leading to the term “cheater’s Akin.” Today, we consider the terminology “Akin bunionectomy” outdated. The correct terminology to use is “Akin procedure/osteotomy” or anatomically as a “hallux osteotomy.”

When Is An Isolated Akin Indicated?

Isolated Akin procedures still occur today but in much less common circumstances. Patients who have an intrinsic deformity of the hallux without a bunion are candidates for an isolated procedure. Pointy toe shoes for women have produced this deformity, which often occurs closer to the interphalangeal joint. Some patients may have “bunions” from a prominent medial eminence of the first metatarsal (with a well aligned metatarsal) along with hallux abduction. These patients may require an Akin procedure along with metatarsal exostectomy, though some would consider this a bunion surgery operation.2 Frey and colleagues reported on initial and long-term results of 45 Akin procedures.2 The authors noted excellent and good results in 89 percent of patients with the most common technical problem in 22 percent of the patients being plantar angulation at the osteotomy site. They acknowledged that an Akin procedure alone is rarely indicated to correct hallux valgus and in most patients, one must perform a proximal phalangeal osteotomy in combination with some other procedure to correct all components of the hallux valgus deformity.  One should not perform an isolated Akin to correct for a bunion deformity when there is significant medial deviation of the first metatarsal (metatarsus primus adductus), meaning an “increased” intermetatarsal angle. Performing an isolated Akin in this circumstance would be a considered a cheater’s Akin, especially with larger intermetatarsal angles. Similarly, adding a McBride (exostectomy and adductor release) to an Akin in these same circumstances doesn’t particularly justify the combination procedures. Of course, there are clinical situations (age, weightbearing requirements, bone stock, etc.) in which surgeons utilize these procedures but, in general, one should avoid the cheater’s Akin as a primary means of correction.

One should not perform an isolated Akin to correct for a bunion deformity when there is significant medial deviation of the first metatarsal (metatarsus primus adductus), meaning an “increased” intermetatarsal angle. Performing an isolated Akin in this circumstance would be a considered a cheater’s Akin, especially with larger intermetatarsal angles. Similarly, adding a McBride (exostectomy and adductor release) to an Akin in these same circumstances doesn’t particularly justify the combination procedures. Of course, there are clinical situations (age, weightbearing requirements, bone stock, etc.) in which surgeons utilize these procedures but, in general, one should avoid the cheater’s Akin as a primary means of correction.

When To Add An Adjunctive Akin

The main goal of bunion surgery, from a positional standpoint, is to realign the first metatarsophalangeal joint (MPJ). This means creating a congruent joint where the midline of the osseous structures crosses the midline of the joint. With realignment of the first ray (and the cartilage on the first metatarsophalangeal joint), the weightbearing forces should pass through or near the center of the joint. This requires the big toe to be relatively well aligned with the underlying joint. Many patients, especially women, seem to want the big toe to be perfectly straight. In my experience, a perfectly straight big toe does not function as well as a toe that is slightly abducted. Also, surgeons need to consider the spacing of the toes in the perspective of the entire foot to balance the overall “look” of the foot. It is my opinion that balancing the big toe to the foot is akin to balancing the nose to the face. One can add the Akin procedure to a distal metatarsal osteotomy bunionectomy and/or a Lapidus bunionectomy.3,4  Unless there is obvious intrinsic deformity of the proximal phalanx, one should consider the Akin after performing the metatarsal correction. If the toe is still deviated (provided the metatarsal correction was adequate), then perform the Akin procedure. Keep in mind that one can achieve additional positional correction with capsule closure of the metatarsophalangeal joint.

Unless there is obvious intrinsic deformity of the proximal phalanx, one should consider the Akin after performing the metatarsal correction. If the toe is still deviated (provided the metatarsal correction was adequate), then perform the Akin procedure. Keep in mind that one can achieve additional positional correction with capsule closure of the metatarsophalangeal joint.

Should You Perform A Proximal, Midshaft Or Distal Akin?

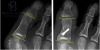

Theoretically, the surgeon would determine the location of where to perform the Akin procedure by identifying where the level of deformity is located within the proximal phalanx. Accomplish this by drawing a line bisecting the medullary shaft and compare that to a line that is perpendicular to the joint line of the articular side of the phalanx. The three options are: proximal, midshaft or distal. In the rare exception of a severe intrinsic deformity of the hallux at the distal or proximal side, it is my experience that a midshaft oblique osteotomy that extends into a metaphysis is the best method of correction. In most cases, the osteotomy is an adjunct to the bunion correction so theoretically, extreme degrees of deformity correction are not necessary and center of rotation of angulation (CORA) corrections of such a small bone are unnecessary in clinical practice. Most commonly, surgeons will perform wedge osteotomies of the proximal phalanx of the hallux with a lateral hinge. The benefits of the hinge are to act a single point of fixation when one combines this with another fixation source (i.e., screw, wire, staple). Through and through osteotomies can be beneficial to “dial” in the correction when the surgeon performs these in the transverse plane. Intraoperative fluoroscopy is extremely helpful to assess that the first MPJ and the hallux interphalangeal joints are parallel.

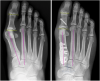

A Step-By-Step Guide To Effective Fixation For An Akin

There are several methods to fixate an Akin osteotomy and one can typically determine the best method by the orientation and location of the osteotomy.5  Surgeons can easily fixate oblique osteotomies with a screw. Transverse osteotomies lend themselves to staple fixation although surgeons trained on monofilament wire find that technique satisfactory.6 Percutaneous K-wire fixation is much less common since rigid internal fixation is commonplace. Surgeons have also used sutures. Roy and Tan noted that suture fixation has the advantages of a lower implant signature and a lower cost.7 The authors conceded that the thin cortex of the phalanx can be prone to failure during suture application. Surgeons often do not prefer plate fixation of primary hallux osteotomies as plates are bulkier than screw fixation and can cause soft tissue irritation. Low profile plates may be a more practical plating solution.

Surgeons can easily fixate oblique osteotomies with a screw. Transverse osteotomies lend themselves to staple fixation although surgeons trained on monofilament wire find that technique satisfactory.6 Percutaneous K-wire fixation is much less common since rigid internal fixation is commonplace. Surgeons have also used sutures. Roy and Tan noted that suture fixation has the advantages of a lower implant signature and a lower cost.7 The authors conceded that the thin cortex of the phalanx can be prone to failure during suture application. Surgeons often do not prefer plate fixation of primary hallux osteotomies as plates are bulkier than screw fixation and can cause soft tissue irritation. Low profile plates may be a more practical plating solution.

Common Mistakes When Considering An Akin

The Akin is a powerful procedure that can give the illusion of correcting a bunion by simply repositioning the toe. Accordingly, it is not uncommon for surgeons to choose to perform bunion procedures that may not fully correct the intermetatarsal angle and may compensate for the shortcoming with an Akin procedure. An example of this is when surgeons perform a distal first metatarsal osteotomy in conjunction with an Akin procedure for a bunion with a large intermetatarsal angle. While this may work in clinical practice, it is something to strongly consider avoiding as this combination may be more prone to cause bunion recurrence down the road.

Pertinent Insights On Using The Akin In Revision Bunion Surgery

I have found the Akin osteotomy to be particularly useful in revision bunion surgery, whether or not the patient previously had an Akin. Of course, an overcorrected Akin is the exception to this. Patients presenting with recurrent bunions complain of a toe that is still deviated or complain of the continued presence of a bunion. The possible reasons for recurrence are as follows: continued increased intermetatarsal angle, persistent medial eminence, unaddressed proximal articular set angle (PASA) deviation, incomplete adductor release and/or hallux interphalangeus. In my experience with recurrent bunions, there is a multifactorial cause for their recurrence.  The most common cause of recurrent bunions that I treat involves a distal metatarsal osteotomy or Lapidus malunion. Patients undergoing both of these procedures often have had a previous McBride and there tends to be some scar tissue within the first MPJ, which can limit the ability to gain a completely congruent joint. Once I correct the intermetatarsal angle (with another procedure) and a revision McBride procedure, the Akin procedure can provide additional correction to achieve a more rectus toe.

The most common cause of recurrent bunions that I treat involves a distal metatarsal osteotomy or Lapidus malunion. Patients undergoing both of these procedures often have had a previous McBride and there tends to be some scar tissue within the first MPJ, which can limit the ability to gain a completely congruent joint. Once I correct the intermetatarsal angle (with another procedure) and a revision McBride procedure, the Akin procedure can provide additional correction to achieve a more rectus toe.

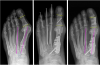

How To Repair An Overcorrected Akin

As with any osteotomy, the Akin osteotomy can also be subject to overcorrection. An overcorrected Akin does not produce a hallux varus per se. Rather, it produces a toe with an adducted tip. The hallux toenail will generally dictate an overcorrection and one often identifies it intraoperatively, although it can become more pronounced postoperatively. It is best to address overcorrection sooner than later. As the Akin osteotomy tends to be a closing wedge procedure, correcting the overcorrection often involves adding bone graft to create an opening wedge. If the surgeon identifies this during the index operation, he or she can replace the initial bone from the wedge or a portion of it back into the osteotomy. In the subacute stage, before the osteotomy has healed, one can still add bone graft but the source is either cadaveric or autogenous. Healed malunions require a new osteotomy and, depending on the clinical scenario, can be a medial opening wedge or lateral closing wedge. The fixation for revision Akin procedures depends on the correction that the surgeon is trying to achieve and whether one has added bone graft. In my experience, plate fixation occurs most often for the revision Akin because there is previous hardware that one is removing and this limits the availability for new hardware. Of course, the specific clinical scenario dictates the hardware choice. Locking plates may provide additional stability and a “T” or “L” plate configuration can fit a variety of osteotomies.

In Summary

The Akin is an adjunct to bunion surgery and by itself has limited use in bunion surgery today. Since the Akin procedure is such a powerful correction to produce a clinically straight toe, surgeons should be cautious to rely too much on the Akin for bunions. It is better to correct the true underlying cause of the bunions rather than provide a cheating solution. However, the Akin procedure is a necessary and vital component to bunion surgery, and is probably underutilized today. Dr. Blitz, creator of the Bunionplasty® procedure, is a Fellow of the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons, and is board-certified in Foot Surgery and Reconstructive Rearfoot Surgery by the American Board of Foot & Ankle Surgery. Dr. Blitz is in private practice in both Midtown Manhattan, New York, and in Beverly Hills, Calif.

To learn more about bunion surgery by Dr. Blitz, please visit www.BunionSurgeryNY.com.

References 1. Rettedal D, Lowery NJ. Proximal phalangeal osteotomies for hallux abductovalgus deformity. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2014;31(2):213-20. 2. Frey C, Jahss M, Kummer FJ. The Akin procedure: an analysis of results. Foot Ankle. 1991;12(1):1-6. 3. Lechler P, Feldmann C, Köck FX, Schaumburger J, Grifka J, Handel M. Clinical outcome after Chevron-Akin double osteotomy versus isolated Chevron procedure: a prospective matched group analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132(1):9-13. 4. Garrido IM, Rubio ER, Bosch MN, González MS, Paz GB, Llabrés AJ. Scarf and Akin osteotomies for moderate and severe hallux valgus: clinical and radiographic results. Foot Ankle Surg. 2008;14(4):194-203. 5. McGarvey SR. Internal fixation of the Akin osteotomy. Foot Ankle Int. 1995;16(3):172-3. 6. Walter RP, James S, Davis JR. Akin osteotomy: good staple positioning. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2012;94(5):371. 7. Roy SP, Tan KJ. A modified suture technique for fixation of the Akin osteotomy. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2013;52(2):276-8. Editor’s note: For further reading, see “A Closer Look At An Emerging Fixation Option For The Akin Osteotomy” in the July 2010 issue of Podiatry Today, the April 2012 DPM Blog, “Secrets To Performing Bunion Surgery That Will Stand The Test Of Time” by William Fishco, DPM, FACFAS, “When Bunion Surgery Fails” in the October 2013 issue or “Which Bunionectomy Technique Provides The Most Advantages?” in the January 2013 issue. Access the archives at www.podiatrytoday.com.